One meets in passing a vast roster of famous figures of the international and artistic set. The scene shifts from Hollywood to the home she loved the best in Versailles. Bemelmans draws a portrait in extremes, through apt descriptions, through hilarious anecdote, through surprisingly sympathetic and understanding bits of appreciation. Lady Mendl was an incredible person,- self-made in proper American tradition on the one hand, for she had been haunted by the poverty of her childhood, and the years of struggle up from its ugliness,- until she became synonymous with the exotic, exquisite, worshipper at beauty's whrine. And his hostess was Lady Mendl (Elsie de Wolfe), arbiter of American decorating taste over a generation. For Bemelmans was "the man who came to cocktails". (photos and line drawings)Īn extravaganza in Bemelmans' inimitable vein, but written almost dead pan, with sly, amusing, sometimes biting undertones, breaking through. A good overview of one of the great intellectual puzzles of modern history. Finally he succeeded, and the greatest problem in mathematical history was laid to rest.

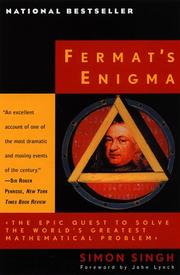

Then a flaw in the proof presented itself-and Wiles went back to work for over a year to patch it up. He announced his proof at a famous mathematical congress in Cambridge, England-a truly great moment in mathematical history. But it was the Taniyama-Shimuru conjecture that gave Wiles the opening to solve the problem after working in isolation for seven years. Finally, in the 1950s, two Japanese mathematicians came up with a conjecture concerning elliptical equations that, at the time, seemed to have nothing to do with Fermat's problem. Singh gives a colorful and generally easy-to-follow summary of much of the mathematical theory that was generated in attempts to prove Fermat's conjecture. Generations of the finest mathematicians failed to corroborate his claim. Singh traces the roots of the problem in ancient geometry, from the school of Pythagoras (whose famous theorem is clearly its inspiration) up to the flowering of mathematics in the Renaissance, when Fermat, a French judge who dabbled in number theory, stated the problem and claimed to have found a proof of it. As a schoolboy in England, Wiles stumbled across a popular account of Fermat's puzzle: the assertion that no pair of numbers raised to a power higher than two can add up to a third number raised to the same power. As one of the producers of the BBC Horizons show on how the 300-year-old puzzle was solved, Singh had ample opportunity to interview Andrew Wiles, the Princeton professor who made the historic breakthrough. The proof of Fermat's Last Theorem has been called the mathematical event of the century this popular account puts the discovery in perspective for non-mathematicians.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)